Want to hear a story about how small changes can make a big impact on your customer experience and bottom line?

This is the tale of how one tiny button tweak led to a whopping $300M in annual revenue for a company.

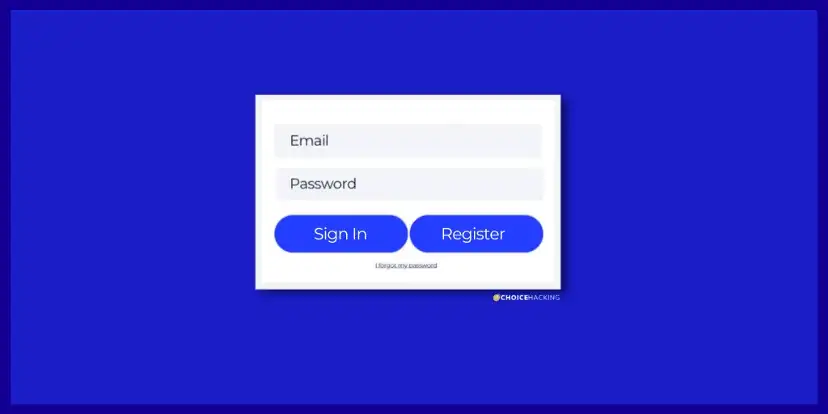

It all began with the company’s purchase process. The design was pretty basic, featuring a straightforward form that prompted users to sign in or register before finishing their purchase.

The problem was that users were required to create an account on the site to make any purchase. The design and marketing teams believed that “users won’t mind registering because next time they shop the process will be easier and faster,” but when the checkout was launched, they found that this was not the case.

When the site forced people to register for an account before buying, they simply didn’t buy anything. They told researchers, “I’m not here to be in a relationship.” This was a clear indication that the company was missing out on a huge amount of revenue by making the registration process mandatory.

Here’s what happened when the new design went live:

- 45% increase in the number of users who completed a purchase

- In this first year, the site made $300M more in revenue

But why did such a tiny tweak have such a big impact?

It’s down to a concept called Friction.

What is Friction?

Friction refers to any barriers that impede a customer from achieving their goals. It can manifest in various forms such as:

- Asking a user to think too much, which can increase their cognitive load.

- Presenting customers with too many options, which can lead to choice overload.

Regardless of the source, friction makes it harder for customers to get what they want. By reevaluating our assumptions about what users want and observing their actions (not just relying on their statements), we can uncover opportunities that have been in front of us all along.

It’s important to be aware of friction and actively work to minimize it in order to improve the customer experience and increase revenue.

Why Friction Isn’t Always a Bad Thing

While friction is often seen as a negative aspect of the customer experience, it is not always bad. In fact, some friction points can create long-term value for the customer, increase desire for the product, or have other benefits for the business.

An example of friction working in a brand’s favor is the Hermès Birkin bag. These bags are incredibly expensive, with prices ranging from $20,000 to $300,000 and beyond.

The high cost and limited availability of the bags create a sense of exclusivity and desirability, making them highly sought-after luxury items. The friction created by the high cost and limited availability of the bags drives desire for the product, ultimately benefiting the brand.

It’s important to understand that not all friction is bad, and sometimes it can even be beneficial for the business. It’s crucial to evaluate each friction point individually and consider the potential long-term effects it may have on the customer experience and the business before removing it.

Exactly, the Birkin bags are highly desirable, and the friction points in the purchasing process, such as the high cost and long waitlist, only add to the allure of the bags. It creates a sense of exclusivity and desirability, which makes them highly sought-after luxury items.

The high cost and limited availability of the bags drive desire for the product, ultimately benefiting the brand. The long waitlist and the exclusivity of the waitlist, in particular, create a perception that only a select few can have access to the product, making it even more desirable.

This is a prime example of how friction can be beneficial for a brand, as it creates a sense of exclusivity and desirability that drives demand.

The Bottom Line

As we’ve established, friction can be a positive or negative force depending on its intention. And using it to guide users to the “correct” path or behavior can unlock value (or destroy customer relationships). So we need to use it wisely.

We can start by asking ourselves if a particular point of friction is creating value for the customer in the long-run — even if it’s annoying in the moment. Often “good” friction in a user experience includes moments like:

- When users are performing high-risk actions, like entering personal data or confirming shipping information.

- When users are likely to be on autopilot, and need to get their “head in the game” and pay attention to something that’s required of them, like taking an action that can’t be walked back later.

Introducing more friction in a process can also just be the right thing to do.

For example, for many years McDonald’s would ask customers if they wanted to “supersize” their meals when they ordered — meaning that they’d get an extra-large drink and an extra-large fry with their burger. Because of the pressure of standing in line people were in quick decision-making mode. The brand made it too easy for customers to say “yes” and over-order.

In the early 2000s, a more health-conscious McDonald’s took the Supersize off the menu and stopped asking customers if they wanted to “supersize” their meals. This decision was based on the company’s commitment to promoting healthier options, and it helped reduce the number of high-calorie options available to customers.

Overall, friction can be a powerful tool in the design of user experiences, but it’s important to use it with intention and consider its impact on the customer. It’s important to be mindful of how friction affects the user’s journey and make decisions based on the long-term value that it creates for the customer.

To decide if a point of friction needs to be removed, we can start by asking ourselves if there is a point to the user frustration.

“Bad” friction might include making what should be a simple process (buying a product) into something that’s too long and mentally taxing to have any benefit — as in our $300M button example.

If your users are abandoning carts at a high rate, taking a long time to decide between options, skip onboarding screens (walkthroughs), or quit filling out forms in the middle of a process, it’s an indication that these points of friction are “bad” and if fixed would improve the experience for users and the brand’s bottom line.